Ulteriori informazioni

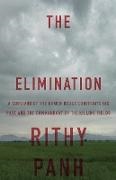

Zusatztext 77497794 Informationen zum Autor Rithy Panh is an internationally and critically acclaimed documentary film director and screenwriter. His films include S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine and Rice People ! the first Cambodian film to be submitted for an Oscar! among others. His newest documentary was inspired by The Elimination. Christophe Bataille is a French novelist. His works include the award-winning Annam ! Hourmaster ! and Absinthe . He has been an editor at Editions Grasset since 1997. Klappentext From the internationally acclaimed director of S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine! a survivor's autobiography that confronts the evils of the Khmer Rouge dictatorship. Rithy Panh was only thirteen years old when the Khmer Rouge expelled his family from Phnom Penh in 1975. In the months and years that followed! his entire family was executed! starved! or worked to death. Thirty years later! after having become a respected filmmaker! Rithy Panh decides to question one of the men principally responsible for the genocide! Comrade Duch! who's neither an ordinary person nor a demon-he's an educated organizer! a slaughterer who talks! forgets! lies! explains! and works on his legacy. This confrontation unfolds into an exceptional narrative of human history and an examination of the nature of evil. The Elimination stands among the essential works that document the immense tragedies of the twentieth century! with Primo Levi's If This Is a Man and Elie Wiesel's Night. In the interviews we often bring up the works of Karl Marx, which Duch knows and admires. Me: “Mr. Duch, who are the closest followers of Marxism?” Duch: “The illiterate.” People who can’t read are the “closest” followers of Marxism. They’re the ones who are in arms. And, I may add, they’re the ones who obey. Those who read have access to words, to history, and to the history of words. They know that language shapes, flatters, conceals, enthralls. He who reads reads language itself; he perceives its duplicity, its cruelty, its betrayal. He knows that a slogan is just a slogan. And he’s seen others. ' In 1975, I was thirteen years old and happy. My father had been the chief undersecretary to several ministers of education in succession; now he was retired, and a member of the senate. My mother cared for their nine children. My parents, both of them descended from peasant families, believed in knowledge. More than that: they had a taste for it. We lived in a house in a suburb close to Phnom Penh. Ours was a life of ease, with books, newspapers, a radio, and eventually a black-and-white television. I didn’t know it at the time, but we were destined to be designated— after the Khmer Rouge entered the capital on April 17 of that year—as “new people,” which meant members of the bourgeoisie, intellectuals, landowners. That is, oppressors who were to be reeducated in the countryside—or exterminated. Overnight I become “new people,” or (according to an even more horrible expression) an “April 17.” Millions of us are so designated. That date becomes my registration number, the date of my birth into the proletarian revolution. The history of my childhood is abolished. Forbidden. From that day on, I, Rithy Panh, thirteen years old, have no more history, no more family, no more emotions, no more thoughts, no more unconscious. Was there a name? Was there an individual? There’s nothing anymore. What a brilliant idea, to give a hated class a name full of hope: new people . This huge group will be transformed by the revolution. Transmuted. Or wiped out forever. As for the “old people” or “ordinary people” they’re no longer backward and downtrodden, they become the model to follow—men and women working the lands their ancestors worked or bending over machine tools, revolutionaries rooted in practical...