Read more

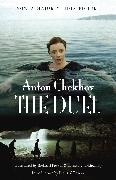

Informationen zum Autor About the Translators Together! Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky! translated works by Tolstoy! Dostoevsky! Checkhov! and Gogol. They were twice awarded the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Prize (for their versions of Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov and Tolstoy's Anna Karenina )! and their translation of Dostoevsky's Demon was one of three nominees for the same prize. They are married and live in France. Klappentext Includes a new forward by the screenwriter Mary Bing In Anton Chekhov's The Duel the escalating animosity between two men with opposed philosophies of life is played out against the backdrop of a seedy resort on the Black Sea coast. Laevsky is a dissipated romantic given to gambling and flirtation; he has run off with another man's wife! the beautiful but vapid Nadya! and now finds himself tiring of her. The scientist von Koren is contemptuous of Laevsky; as a fanatical devotee of Darwin! von Koren believes the other man to be unworthy of survival and is further enraged by his treatment of Nadya. As the confrontation between the two becomes increasingly heated! it leads to a duel that is as comically inadvertent as it is inevitable. Masterfully translated by the award-winnning Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky! The Duel is one of the most subtle examples of Chekhov's narrative art. i it was eight o'clock in the morning-the time when officers, officials, and visitors, after a hot, sultry night, usually took a swim in the sea and then went to the pavilion for coffee or tea. Ivan Andreich Laevsky, a young man about twenty-eight years old, a lean blond, in the peaked cap of the finance ministry and slippers, having come to swim, found many acquaintances on the shore, and among them his friend the army doctor Samoilenko. With a large, cropped head, neckless, red, big-nosed, with bushy black eyebrows and gray side-whiskers, fat, flabby, and with a hoarse military bass to boot, this Samoilenko made the unpleasant impression of a bully and a blusterer on every newcomer, but two or three days would go by after this first acquaintance, and his face would begin to seem remarkably kind, nice, and even handsome. Despite his clumsiness and slightly rude tone, he was a peaceable man, infinitely kind, good- natured, and responsible. He was on familiar terms with everybody in town, lent money to everybody, treated everybody, made matches, made peace, organized picnics, at which he cooked shashlik and prepared a very tasty mullet soup; he was always soliciting and interceding for someone and always rejoicing over something. According to general opinion, he was sinless and was known to have only two weaknesses: first, he was ashamed of his kindness and tried to mask it with a stern gaze and an assumed rudeness; and second, he liked it when medical assistants and soldiers called him "Your Excellency," though he was only a state councillor. "Answer me one question, Alexander Davidych," Laevsky began, when the two of them, he and Samoilenko, had gone into the water up to their shoulders. "Let's say you fell in love with a woman and became intimate with her; you lived with her, let's say, for more than two years, and then, as it happens, you fell out of love and began to feel she was a stranger to you. How would you behave in such a case?" "Very simple. Go, dearie, wherever the wind takes you- and no more talk." "That's easy to say! But what if she has nowhere to go? She's alone, no family, not a cent, unable to work . . ." "What, then? Fork her out five hundred, or twenty-five a month-and that's it. Very simple." "Suppose you've got both the five hundred and the twenty-five a month, but the woman I'm talking about is intelligent and proud. Can you possibly bring yourself to offer her money? And in what form?" Samoilenko was about to say something, but just th...