Read more

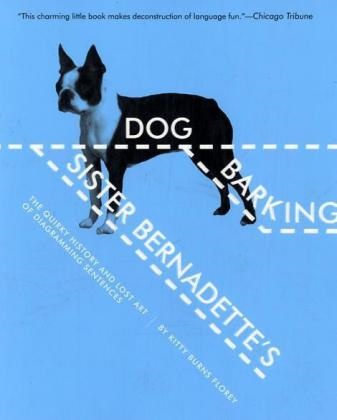

Zusatztext PRAISE FOR SISTER BERNADETTE’S BARKING DOG "Florey writes with verve about the nuns who taught her to render the English language as a mess of slanted lines, explains how diagrams work, and traces the bizarre history of the men who invented this odd pedagogical tool . . . It’s a great read."-- Slate "This gem from copyeditor Florey is a bracing ode to grammar: it’s laced with a survivor’s nostalgia for classrooms ruled by knuckle-cracking nuns who knew their participles."— People Informationen zum Autor KITTY BURNS FLOREY, a veteran copyeditor, is the author of nine novels and many short stories and essays. A longtime Brooklyn resident, she now divides her time between central Connecticut and upstate New York with her husband, Ron Savage. Klappentext A delightfully offbeat history of the art and science of sentence diagramming by a veteran copyeditor and writer. Grumpy grammarians, crossword-puzzle aficionados, and lovers of language will appreciate this book. In its heyday, sentence diagramming was wildly popular in grammar schools across the country. Kitty Burns Florey learned the method in sixth grade from Sister Bernadette: "It was a bit like art, a bit like mathematics. It was a picture of language. I was hooked." Florey explores the sentence-diagramming phenomenon, including its humble roots at the Brooklyn Polytechnic, its "balloon diagram" predecessor, and what diagrams of famous writers' sentences reveal about them. Along the way, Florey offers up her own commonsense approach to learning and using good grammar. Charming, fun, and instructive, Sister Bernadette's Barking Dog will be treasured by all kinds of readers. Leseprobe chapter 1 ENTER THE DOG Diagramming sentences is one of those lost skills, like darning socks or playing the sackbut, that no one seems to miss. When it was introduced in an 1877 text called Higher Lessons in English by Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg, it swept through American public schools like the measles, embraced by teachers as the way to reform students who were engaged in (to take Henry Higgins slightly out of context) “the cold-blooded murder of the English tongue.” By promoting the beautifully logical rules of syntax, diagramming would root out evils like “him and me went” and “I ain’t got none,” until everyone wrote like Ralph Waldo Emerson, or at least James Fenimore Cooper.1 1 I’m thinking here of Mark Twain’s famous and still highly entertaining essay, “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses,” in which Twain concludes that “in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 literary offenses out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” But Wilkie Collins called Cooper “the greatest artist in the domain of romantic fiction in America.” Even in my own youth, many years after 1877, diagramming was serious business. I learned it in the sixth grade from Sister Bernadette. Sister Bernadette: I can still see her, a tiny nun with a sharp pink nose, confidently drawing a dead-straight horizontal line like a highway across the blackboard, flourishing her chalk in the air at the end of it, her veil flipping out behind her as she turned back to the class. We begin , she said, with a straight line. And then, in her firm and saintly script, she put words on the line, a noun and a verb—probably something like dog barked . Between the words she drew a short vertical slash, bisecting the line. Then she drew a road—a short country lane—that forked off at an angle under the word dog , and on it she wrote The . That was it: subject, predicate, and the little modifying article that civilized the sentence—all of it made into a picture that was every bit as clear and informative as an actual portrait of a beagle in midwoof. The th...