Read more

Late April, 1945. The war is over, yet Dr Doll, a loner and 'moderate pessimist', lives in constant fear. By night, he is haunted by nightmarish images of the bombsite in which he is trapped - he, and the rest of Germany. More than anything, he wishes to vanquish the demon of collective guilt, but he is unable to right any wrongs, especially in his position as mayor of a small town in north-east Germany that has been occupied by the Red Army.

Dr Doll flees for Berlin, where he finds escape in a morphine addiction: each dose is a 'small death'. He tries to make his way in the chaos of a city torn apart by war, accompanied by his young wife, who shares his addiction. Fighting to save two lives, he tentatively begins to believe in a better future.

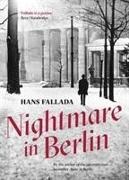

Written with Fallada's distinctive power and vividness, Nightmare in Berlin captures the demoralised and desperate atmosphere of post-war Germany in a way that has never been matched or surpassed.

About the author

Rudolf Ditzen alias Hans Fallada , geb. 1893 in Greifswald als Sohn eines hohen Justizbeamten, besuchte ohne Abschluss das humanistische Gymnasium und absolvierte eine landwirtschaftliche Lehre. Von 1915-25 war er Rendant auf Rittergütern, Hofinspektor, Buchhalter, von 1928-31 Adressenschreiber, Annoncensammler, Verlagsangestellter. 1920 Roman-Debüt 'Der junge Goedeschal', seit 1931 freiberuflicher Schriftsteller. Mit dem vielfach übersetzten Roman 'Kleiner Mann was nun?' (1932) wurde Fallada weltbekannt. In der Zeit des Faschismus lebte er als 'unerwünschter Autor' zurückgezogen auf seinem Sechs-Morgen-Anwesen in Mecklenburg. 1945 siedelte er nach Berlin über und starb dort 1947.§Weitere wichtige Werke: 'Bauern, Bonzen und Bomben' (1931), 'Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frißt' (1934), 'Wolf unter Wölfen' (1937), 'Der eiserne Gustav' (1938), 'Geschichten aus der Murkelei' (1938), 'Jeder stirbt für sich allein' (1947).

Summary

Available for the first time in English, here is an unforgettable portrayal by a master novelist of the physical and psychological devastation wrought in the homeland by Hitler’s war.

Late April, 1945. The war is over yet Dr Doll, a loner and ‘moderate pessimist’, lives in constant fear. By night, he is haunted by nightmarish images of the bombsite in which he is trapped — he, and the rest of Germany. More than anything, he wishes to vanquish the demon of collective guilt, but he is unable to right any wrongs, especially in his position as mayor of a small town in north-east Germany that has been occupied by the Red Army.

Dr Doll flees for Berlin, where he finds escape in a morphine addiction: each dose is a ‘small death’. He tries to make his way in the chaos of a city torn apart by war, accompanied by his young wife, who shares his addiction. Fighting to save two lives, he tentatively begins to believe in a better future.

Written with Fallada’s distinctive power and vividness, Nightmare in Berlin captures the demoralised and desperate atmosphere of post-war Germany in a way that has never been matched or surpassed.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut which is funded by the German Ministry of the Arts.

Foreword

Available for the first time in English, here is an unforgettable portrayal by a master novelist of the physical and psychological devastation wrought in the homeland by Hitler's war.

Additional text

‘A compressed epic of despair, venality, shame, and endurance, this “strong book about a weak human being”, like most Fallada novels, mirrors its author’s travails … The novel is driven by these surges of emotion, but Fallada keeps our gaze on everyday details, on petty betrayals and intimate crimes … Fallada’s corrosive wit — used sparingly in this novel and to devastating effect — is oddly affecting. It draws us closer to these characters even as they surrender to the oblivion of morphine or to the macabre regimen of the sanatorium … “Life goes on, always”, he concludes. But Fallada’s tightly constructed novel — a snug nesting doll of horror within horror — makes even that bland assertion seem foolish.’