Read more

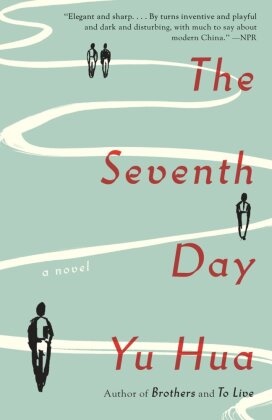

Zusatztext “Elegant and sharp. . . . By turns inventive and playful and dark and disturbing! with much to say about modern China.” —NPR “Surreal. . . . Yu’s most devastating critique of the new Chinese reality.” — The New York Times Book Review “Entertaining. . . . Intriguing. . . . In narrowing his lens! his work carries new urgency.” — The Wall Street Journal “A political allegory for life—and death—experienced in the chaos of a rapidly changing modern China.” — Minneapolis Star Tribune “Plaintive. . . . Moving.” — Grantland “A ghostly walk through contemporary China evokes the human cost of some of the big issues that nation is facing.” — The Toronto Star “Mesmerizing. . . . Internationally award-winning novelist Hua crafts a discerning critique of contemporary Chinese culture through an evocative allegory revealing fates much worse than death.” — Booklist “[A] poignant fable about family bonds made not of blood ties but unbreakable heartstrings. It will assuredly reward Yu’s readers! familiar and new.” — Library Journal (starred review) Informationen zum Autor Yu Hua Klappentext Yang Fei was born on a train as it raced across the Chinese countryside. Lost by his mother, adopted by a young switchman, raised with simplicity and love, he is utterly unprepared for the changes that await him and his country. As a young man, he searches for a place to belong in a nation ceaselessly reinventing itself, but he remains on the edges of society. At forty-one, he meets an unceremonious death, and lacking the money for a burial plot, must roam the afterworld aimlessly. There, over the course of seven days, he encounters the souls of people he's lost. As he retraces the path of his life, we meet an extraordinary cast of characters: his adoptive father, his beautiful ex-wife, his neighbors who perished in the demolition of their homes. Vivid, urgent, and panoramic, Yang Fei's passage movingly traces the contours of his vast nation-its absurdities, its sorrows, and its soul. This searing novel affirms Yu Hua's place as the standard-bearer of Chinese fiction.The fog was thick when I left my bedsit and ventured out alone into the barren and murky city. I was heading for what used to be called a crematorium and these days is known as a funeral parlor. I had received a notice instructing me to arrive by 9:00 a.m., because my cremation was scheduled for 9:30. The night before had resounded with the sounds of collapsing masonry—one huge crash after another, as though a whole line of buildings was too tired to stay standing and had to lie down. In this continual bedlam I drifted fitfully between sleep and wakefulness. At daybreak, when I opened the door, the din suddenly halted, as though just by opening the door I had turned off the switch that controlled the noise. On the door a slip had been posted next to the notices that had been taped there ten days earlier, asking me to pay the electricity and water bills. In characters damp and blurry in the fog, the new notice instructed me to proceed to the funeral parlor for cremation. Fog had locked the city into a single, unchanging guise, erasing the boundaries between day and night, morning and evening. As I walked toward the bus stop, several human figures appeared out of nowhere, only to disappear just as quickly. I cautiously walked ahead for a distance, but found my passage blocked by some kind of sign that appeared to have suddenly grown out of the ground. I thought there ought to be some numbers on it—if the number 203 was there, then this was the stop for the bus I wanted to take. But I couldn’t make out the numbers, even when I felt for them with my hand. When I rubbed my eyes, I seemed to see the number 203, suggesting that this was indeed the stop. But now I had a strange feeling that while my right eye was in the origina...